Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza | Cáseda, 12 October 1918. Madrid, 18 July 2000; he is undoubtedly one of the masters of modern architecture in our country. A controversial, risky, reflective and critical creator of energetic, vehement and passionate verb, whose works are admired and discussed in equal parts, but which have become symbols of modernity.

The festival palace of Santander

On the centenary of the birth of the master, it seems opportune to approach one of his most controversial works and still today criticized and denigrated, coming to be considered as one of the ugliest buildings in Spain.

Situated opposite the bay of the Cantabrian capital, the project is the result of a restricted competition from which Oíza’s proposal came out the winner against those of Navarro Baldeweg, García de Paredes or Rafael Moneo among others and which meant the construction of the building of greater scale carried out in Santander at the time. (see revista COAM)

The Palacio de Festivales santanderino has been criticized without limits or concessions, from the first phases of its execution, long and random, to the final result; branded as a monstrosity for its aesthetics and location, which still awakens today, almost thirty years later, the animosity of locals and visitors.

The final result is far from the winning project of the competition, especially in its scale and programmatic content. The initial proposal, a medium sized music auditorium with a moderate budget, was moulded by the demands of the autonomous government, forcing Sáenz de Oíza to modify the project according to the requests and demands of the then president Juan Hormaechea, who wanted to create a flexible and multidisciplinary building, emblem of Cantabrian culture.

These ups and downs in commissioning and execution triggered the final budget and called into question some of the most important architectural decisions. This gave rise to important functional problems that have conditioned the daily lives of organizers, scenographers, artists and the public. The main access to the building, raised upwards under the stage, the public emerging through the orchestra pit was unfeasible and was used only once, after the inauguration. The lack of space between the rows of seats did not allow the passage of the public, which made it necessary to replace all of them. The large glazed trapeze of the main façade, which allowed the view from the stalls of the bay of Santander hardly opens, as it is incompatible with the assembly of scenographies or acoustic boxes.

“Everything has a motivation, explanations are superfluous. […] the works speak for themselves. The explanations are very good, but the silent explanation that the work produces is the most valuable.”

Thus, between rejection and astonishment, Santander received its long-awaited cultural equipment, that great mass of strange colour, inexplicable for many due to its location, scale and aesthetics, highlighting its completely blind side facades, its four towers and the decorative motifs that frame the accesses to the building.

“¡Oh, Epidauro!”

Although it is true that, contemplating the final result, the criticisms can be considered partly correct, it would not be fair to join the general opinion without first trying to understand the building in its context and clarify the set of decisions and vicissitudes that ended up configuring this controversial work.

Prior to the analysis of the proposal itself, it would be worth highlighting the difficulty involved in the competition from the outset. It was proposed to create a Festival Palace, with a diffuse identity, due to the programmatic demand for flexibility, on a site that, according to the commission of experts of the competition, was unsuitable for a building of these characteristics, small in size (120×40 m), located between party walls, with a notable slope and in direct competition with the School of the Navy. (see revista COAM)

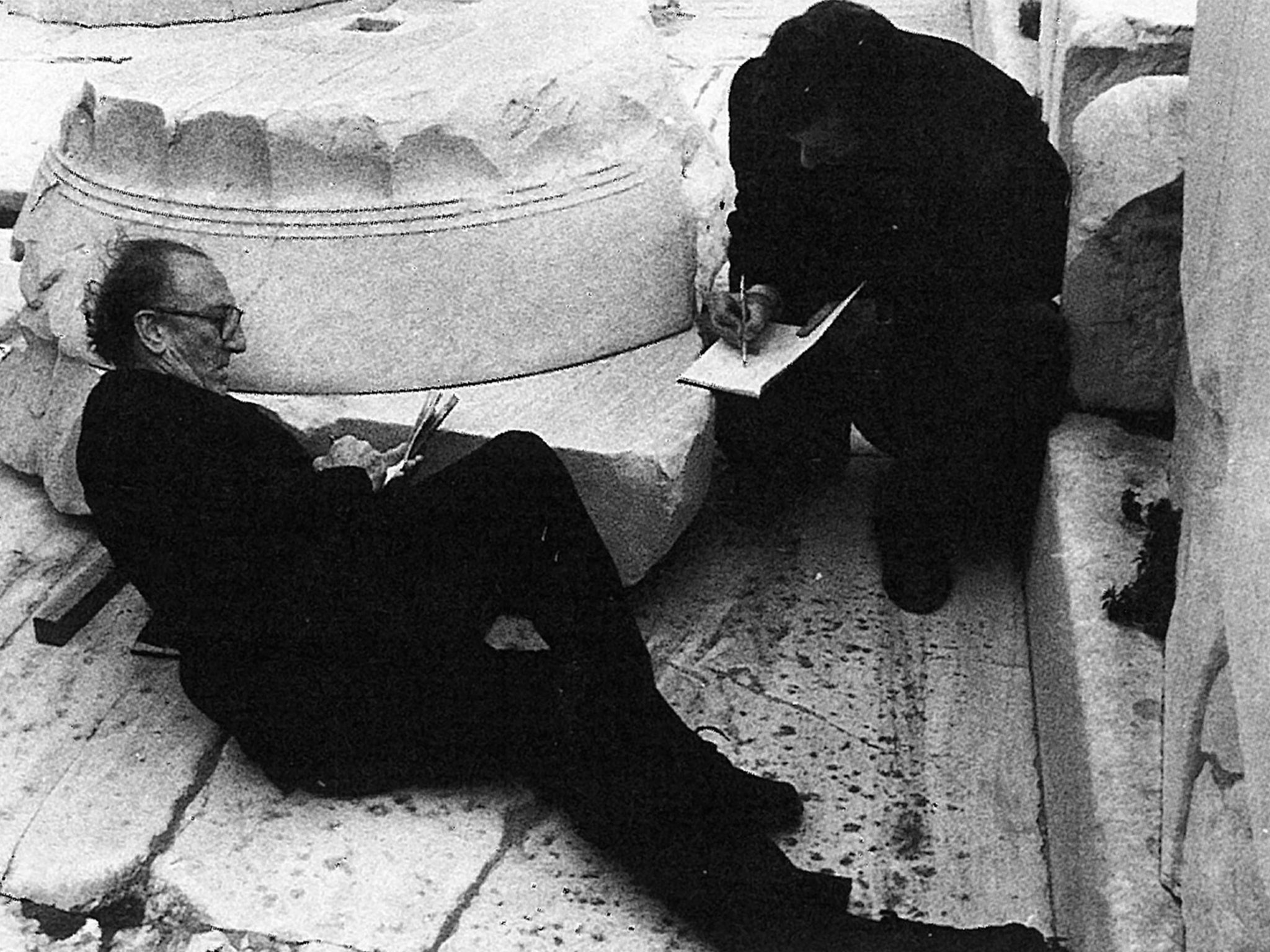

The winning proposal, as Oíza himself relates, is born and arises from the place where it is implanted and is irremediably anchored in front of the bay. The maritime ferries that connect Paseo Pereda with the towns located on the opposite margin are well known in Santander, and everything seems to indicate that it was on one of these routes where the project was conceived, with the first notes of the proposal emerging on the hillside and that, in spite of the changes during construction, they resemble the final result to a great extent.

It is on these routes that the proposal is appreciated in its surroundings and its direct relationship with the seafaring world. It is here where the use of colour is understood: “the boats have marvellous colours and the architectures are anodyne, grey”; the nautical flags whipped by the wind, located in the four corners of the building, which anchor it to the bay and provide it with stability and immutability in front of the main hall that descends following the slope of the plot, sliding towards the sea. (“Imprescindibles” , RTVE)

It is the only time that Oíza faces such a building, and for this he draws on his knowledge of Greek theatre, its relationship with the temple and what it means, connecting with James Stirling and his project for the Stuttgart Gallery (1970-1984). Reference is thus made to the classical world, emphasising the accesses to the building in a playful way, perhaps exaggerated, through the creation of false columns (they hold nothing), but whose message is true, the creation of a place that evokes and represents representation itself.

One of the keys to understanding and valuing this project is its section that, despite the initial adversities, masterfully resolves the conditioning factors of the programme, adapting the main room to the slope of the terrain. A space of great rotundity, defined by the ceiling plane, which incorporates a lighting control system and acoustic reflectors. Where the stage is a filter of the real scene, the horizon of the bay.

But not everything could be voices against the new building. We find in the chronicle of the inauguration, carried out in 1991 by Enrique Franco praises to the proposal, both from a technical and aesthetic point of view, emphasizing its exterior integrated in the profiles of the city.

Beyond criticism and praise, there is no doubt that we are dealing with a complex and provocative building, which arouses rejection and admiration in equal parts, but which leaves no one indifferent. A catalyst for the gazes and opinions of the bay of Santander, it must be understood in its time and circumstances.

After seven years of work, prior to the inauguration of the only theatre by Oíza, the team in charge of endowing the Palace with content asked the architect about all the problems this entailed, to which Oíza responded: “I have made a duck: it flies, but there are birds that fly much higher. Also nothing, but fish swim better. And it walks on the land, but there are animals that make it faster.”. (Oíza for “Diario Montañés”) A good summary of what this building is, which despite its singularities and after a process of adaptation to the final needs, has ended up being configured as the cultural focus it was intended to be.

“What you have to think when you talk about my buildings being controversial, at bottom what I do is to risk […] works of art are always born of who has faced danger, of who has gone to the extreme of an experience.”. (“Imprescindibles”, RTVE)

Author: Miguel Rosón Mozos

Other articles by the collaborator:

Urbanism in three dimensions: The Taray

[expand title=”Bibliography”]

– 1990. Three architectures – Sáenz de Oíza. Documentary series TVE November 22, 1990.

– 2010. Today’s creators – Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oíza. Monographic series Creadores de hoy, Archivo TVE December 24, 2010.

– 2014. Essential – don’t die without going to Ronchamp (Sáenz de Oíza). Indispensable Documentary December 23, 2014.

– Almonacid, R. 2018. On the centenary of Oíza… Blog Fundación Arquia January 17, 2018.

– Balbona, G. 2016. A claim pending since the 1960s. El Diario Montañés 26 April 2016.

– Official College of Architects of Cantabria. Platform for the dissemination of Architectural Heritage.

– Delgado, J. 1989. Sáenz de Oíza meets the critics of his auditorium. El País August 25, 1989.

– The Sketch. Double issue 32-33. 1988 revised and enlarged edition in 2002. 1946 1988 Sáenz de Oíza.

– Photo gallery. 2016. Construction of the Palace of Festivals. El Diario Montañés April 27, 2016.

– Franco, E. 1985. The palace of the Santander Festival, “hanging over the sea”. El País, August 18, 1985.

– Franco, E. 1991. The oratorio “Josué” inaugurated the new Palacio de Festivales de Santander. El País May 1, 1985.

– Gallardo, L. 2016. The Palace Reviews Its History. El Diario Montañés April 25, 2016.

– Lleó, B. 1985. Interview with Sáenz de Oíza. International n3 January 1985.

– Sáenz de Oíza, F.J. 1984. Competition for the Palacio de Festivales de Santander: winning project. Revista Arquitectura del COAM Nº 250 September-October 1984.

– San Miguel, M. 2016. 25 years to tune the Palace of Festivals. El Diario Montañés April 27, 2016.

– Torrijos, P. 2016. The ugliest buildings in Spain (V): the Palacio de Festivales de Cantabria, a snob pharaoh. El Economista.es January 16, 2016.

– Villamor, J.I. 1984. Competition for the Palacio de Festivales de Santander. Magazine Arquitectura del COAM Nº 250 September-October 1984.

[/expand]