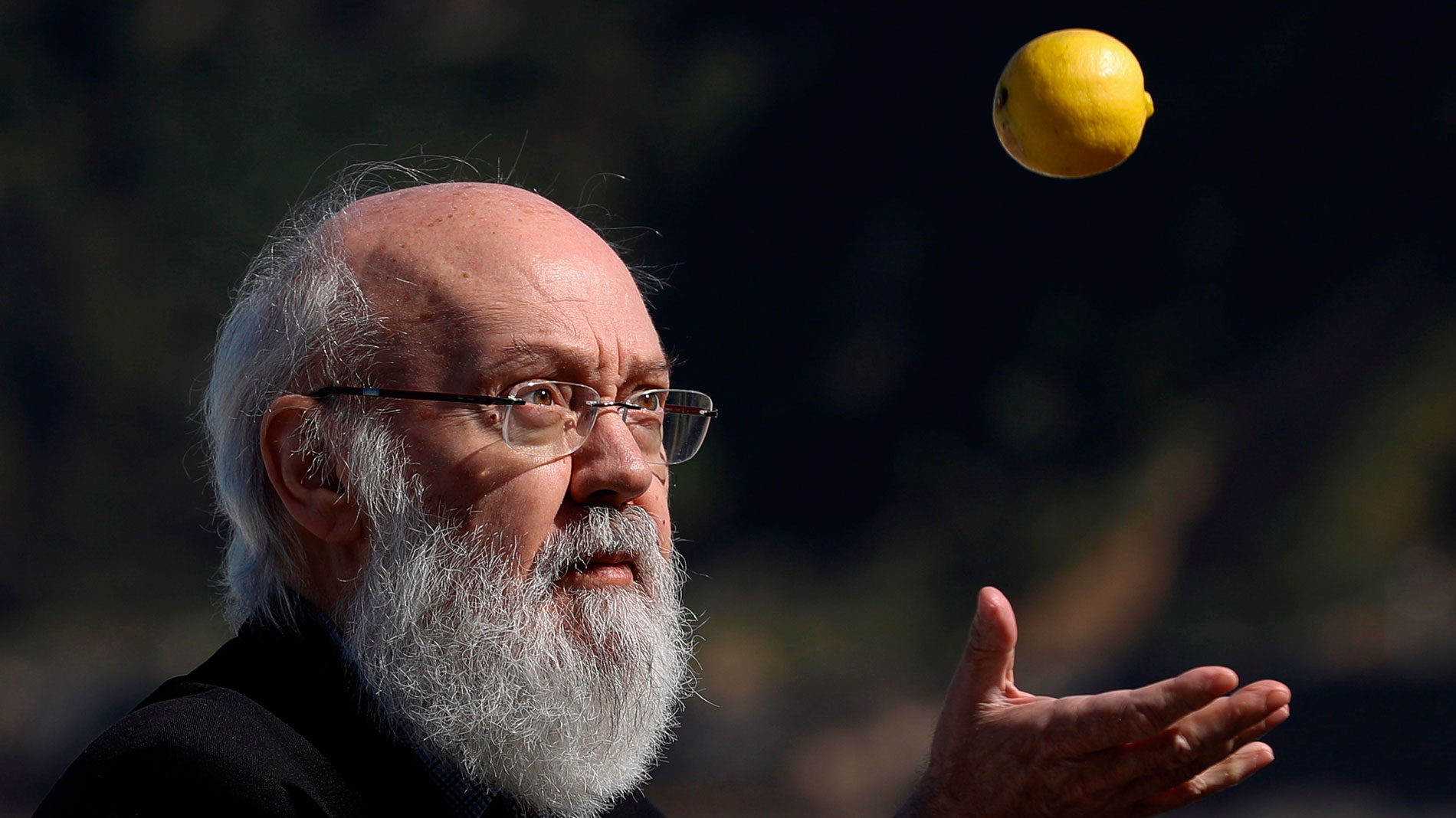

With a kind smile, a thick beard, already gray, and an inseparable hat, José Luis Cuerda seems to tell like an avid liar, but without malice, stories of everyday characters in a world that logic makes us deny; with a temperance that carries his words -and scripts-, as if they were memories lived so long ago that repetition after repetition, have ended up becoming something else, no less real and no less lived in the memory.

Perhaps, to describe the atmosphere of Cuerda’s work, a chapter of Black Mirror should be placed in the deepest Albacete. The director does not treat critique as a form of essay, but introduces factors such as democracy, dictatorship, discrimination, misogyny… into a pucherazo, perhaps, of everyday life and surrealism in order to distill the most outlandish and recognisable situations that we could imagine. All this is born only from the desire to tell stories, freeing the world from an indiscreet eye within a microcosm in which a series of characters are supposed to live in freedom. And evidently, within this universe of its own rules in which London is a small Castilian village or men are born from the ground in terraces, ideas are enclosed that are typical of an awakened man, who has travelled with that curious look, and also fascination, the stage of an entire country in the most important change in its modern history.

The result is a work eager to be read, where the interpretations are answered by the director with an accurate “Pues usted sabrá”. This chronicler maintains a resounding interest in the rest of the arts and architecture, and the interpretations of his work are so personal and varied that anyone -the Cuerda itself, for example- could say that they are inventions, exaggerations and extravagances. Without a hint of scholarship, the Albacete director knows and wants to know more and more. To read, to see, to look… The agile look and the words ballasted but certain.

The “dawn” of Cuerda

His first great success, “Amanece que no es poco” portrays the daily life of a small village where the essential pillars of the community are represented, in an almost stereotyped way, to give veracity to a story that between cyclopean walls and whitewashed houses in the Albacete de la Transición seems to filter and dilute, and we inadvertently attend to a story that little by little ends up filtering in the same way in our minds.

The pretext of the traditional village, the sun in the narrow streets, the countryside and farming, and the dark night, makes the viewer feel instinctively natural in a daily story and predispose to be deceived, to listen to a story exacerbated by definition, perhaps told by one of the characters that appear on screen.

Although 31 years have passed since the director convinced us of this story, it was this past December 2018 when Cuerda released his latest film -by chronology, not by cessation of business- loaded with the same story of stark reality and impossible situations: “Tiempo después”.

Now in 9177, as always with impossible locations and lies to the face that the spectator must assume if he wants to reveal the hidden truth, the film tells the story of a post-apocalyptic society, divided in two: The minuscule elitist force, and the rest of the disinherited -by words of the same Cuerda-. The main force represents the values of a balanced community: The mayor, the power, the worker… And the rest is dispensable, there is no need for variety.

Reduce reality to a minimum

The director, who never felt uncomfortable behind the camera, now shows his more open, more surrealist facet, where he no longer only takes factions of society and agglutinates them into a microcosm like caricatures of themselves: Cutting out the city as a collage and introducing it into the film to produce the disorder that characterises it. Madrid is dismembered within 7000 years, and in the first minutes of the film we see a White Towers that has ended up penetrating the courtyard of the Headquarters of the Cultural Heritage Institute of Spain, shaping through two of the most elitist, modern, controversial buildings of the city, the headquarters of the living forces, which reproduces the reduction of a city to the minimum, its emblem and shame, its characteristic and criticism.

It is that freedom, that freedom to decide that the customs rooted in ancestors and their ideas come from people who are born on earth, or to cut out buildings and arrange them as a kind of monolith in the middle of the wasteland, that characterizes Cuerda’s cinema. Criticism becomes a sigh amidst laughter of situations that could not be described as comedy, but rather as confusion.

José Luis Cuerda is a foolish wise man, an innocent liar who only wants to tell stories, making the spectator reflect with laughter, not after them. Without convoluted or complex plots, the cards -real and false- on the table, and from there, to build a house of cards with no more expectations than to see one more day dawn, which is no small thing.