The 20th century has left us a large number of names that will be remembered in the world thanks to the grain of sand they contributed to our cultural heritage. Iannis Xenakis is one of those names, although he is much better known in the world of music than in architecture. If we mention the name of Charles-Édouard Jeanneret-Gris, it is probable that we will not be located either, but if we call him because of the firm he adopted throughout his life, it will be practically impossible not to know him. Le Corbusier. These two names are our protagonists this week, and in contrast to most of the publications in which his name appears, Le Corbusier will be the accompanist, remaining in the shadow of Xenakis.

The story of Iannis Xenakis is that of a person who gave himself to the world of art from the field of music and mathematics. His link with Le Corbusier was born when he began to work in his studio as an engineer in 1948. The technician showed a “geometric spirit” that fitted in with his master’s way of understanding art, where they were in charge of giving order to nature through the organization of sensations.

The enveloping art

In his constant work with space, Iannis Xenakis understood that there are two arts capable of enveloping the person. These are music and architecture, which are the arts that allow man to inhabit a space.

“To make music or architecture is to create, to generate environments that envelop sound or visually, poems”.

Art, in general, mysteriously communicates and communicates with each other, but poetry, dance, sculpture or painting lack an abstract and asemantic nature, which is detectable in the field of music and architecture. Just as in music language exhibits different heights, durations or dynamics that generate comprehensible sounds for people, architecture works through the construction of volumes that interact with our perception of the environment. And although both are able to say a lot without words, it is sometimes difficult to translate what they transmit into language.

But these two fields are more related than a priori may seem. Unlike the “simple” integration of the arts offered by the Renaissance and Baroque, where architecture was transformed into a canvas or ornacina for other forms of expression, Xenakis worked with music in the same way he did with architecture: creating atmospheres. The pieces of this engineer are capable of filling the environment, they become enveloping art that scratches our insides and explores our most intimate self.

Another of the most remarkable characteristics of this musician was his use of mathematics, or rather geometry, when creating new works. Mathematics is present in music because it is an art based on the rules of proportion, which relates the different tones and durations harmoniously. Iannis Xenakis took this way of understanding music in relation to mathematics to the extreme, working with geometry and making musical “blueprints”. Scores that are as interesting to listen to as they are to observe, showing us the relationships of scale, affinity, or escape of elements that end up generating musical pieces that are exceptionally disturbing.

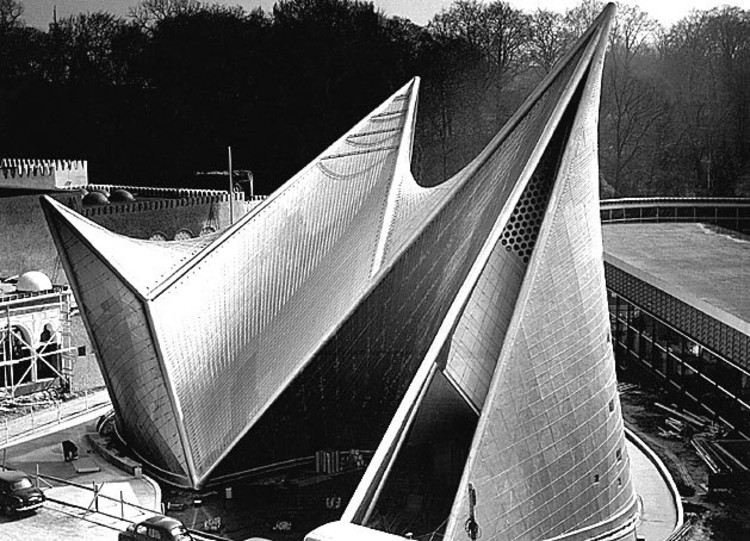

This original way of creating music through mathematics and geometry led him to create pieces that were totally separate from the canons of the moment. Beethoven described nature, Sibelius generated concern about it, but it wasn’t until Xenakis that he was able to represent the visceral being associated with it. Thus, Iannis was not “only” the engineer who collaborated with Le Corbusier in the Philips pavilion in 1958, he was the musician who changed the panorama giving us another new way of creating art.