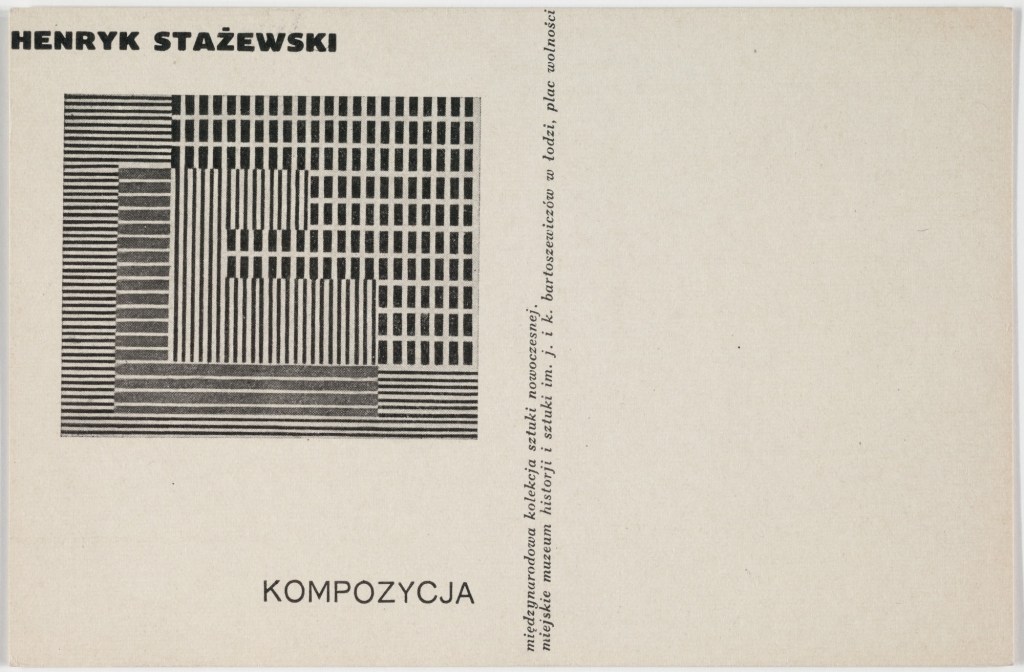

It was the 1960s when Henryk Stażewski, a Polish painter, discovered a new dimension to add to a canvas. The artist begins to use volume as part of his work, working with the relief provided by different materials on the painting. The innovative of the technique was accompanied by the new materials of the moment, these volumes appeared with wood, copper, aluminium, but also with other novel elements, such as plexiglas. This artistic experimentation would be accompanied by the use of fluorescent painting or the use of neon. Artistic experimentation that has a common denominator: Tension.

Jan Tschichold Collection (MoMA), gift from Philip Johnson. Henryk Stażewski.

In Henryk’s work there is an ordered cosmos that, due to the relationship between the different pieces, generates a movement, a tension. This gesture breaks the basic order, areas of greater weight are created in the works, an action that leads our gaze to wander around the piece while trying to understand the existing relationships.

These relationships, first investigated through monochromy, continue their path to more complex bonds through the use of color. Relationships reach their moment of maximum complexity when three-dimensionality appears over the pictorial. Volume that generates shadows projected on the canvas. Time becomes part of the work, being able to appreciate its path through the painting. The tensions are aggravated by the projection left by the subtle volumes, making this movement palpable as well as changing. Finally, a certain scenographic character is recognised in these works, where two planes appear, with the foreground always remaining a protagonist on the canvas, sometimes white.

Production as an obsession

Henryk’s art becomes a systematic experimentation, once he discovers this path, he continues to work on it as if it were an obsession. His works differ thanks to the nuances offered by the use of closed or open ranges of colour, the variety of forms to be used or the position in which they are placed on the canvas. If you review your work, you may remind us of the endless number of models or formats that appear in creative experimentation when you produce architecture. His studio could well be a workshop in which each piece is studied millimetrically to understand how relationships between elements work, and what that means in space.

Walking through his work is a lesson in elements of such importance as the relationships between background-form, content-continent, perimeter-area, tangencies, matrices or plots, elements that, when used with precision, generate that tension that does not leave us indifferent.

The artist’s great pictorial legacy leaves its mark on international culture, being one of the main avant-gardists of Constructivism, as well as transcending as one of the creators of the artistic movement that promotes Geometric Art.

Nowadays, and re-reading his work from the point of view of architecture, he has left us an interesting work in which to learn how to use simple compositional tools to work. From the interpretation of these works of Henryk used as models, to learn to dominate the tensions that generates the order of the different forms or the color in the space. An experimentation that comes to us and still oozes contemporaneity, thus denying that, despite being close to the turn of the century, is marked as obsolete.