The painter of poems, the writer of spots, dancer of words… We can hardly clarify a closed qualifier for the figure of Henri Michaux. Described as serene, smiling and without effusive conversation, this Belgian came to French somewhat taciturn and of elaborated thoughts spent his life looking for the way to explain to us the inexplicable, in a place in which the meaning is lost.

Born in Namur (Belgium) in 1899, Henri begins a journey interested in the human figure. Science seems to be a viable option, opting for medicine, which he soon realised did not respond to the need to understand what was truly human, beyond science.

At the age of 20, he embarks as a cook on a ship bound for South America, where he manages to make his thoughts lucid. After four years, on his return, he published his first article and moved to Paris, where he began to study the work of, among others, Dalí, Klee… Despite the fact that by then his writings, poems and articles had begun to open up a gap in the national panorama, Michaux finally decided to use the tool of plastic art to try to transmit what he did not get through the verb.

From there, he made numerous trips that he wanted to immortalize through the stories he ended up publishing, for example, in his works Ecuador and Un bárbaro en Asia. In one of his trips to South America, Henri met the Argentine writer Jorge Luis Borges with whom, in spite of his extreme differences -perhaps because of what the poles attract- he established a friendship that lasted until the end of the days of both of them, translating this last travel notebook cited and giving him the following prologue:

Around 1935 I met Henri Michaux in Buenos Aires. I remember him as a serene and smiling man, very lucid, of good and not effusive conversation and easily ironic. He did not profess any of the superstitions of that date. He disbelieved of Paris, of literary convents, of the cult, then of rigor, of Pablo Picasso. With an impartial couple, he disbelieved oriental wisdom. All this is confirmed in his book Un barbare en Asie, which I translated into Spanish not as a duty but as a game. He used to amaze us with sad news from Bolivia, where he had resided for a while. In those years he did not suspect what the East would give him or, in a mysterious way, had already given him. He admired the work of Paul Klee and the work of Giorgio de Chirico.

Throughout his long life he exercised two arts: painting and letters. In his last books he combined them. The Chinese and Japanese notion that the ideograms of a poem are composed not only for the ear but also for the sight, suggested him curious experiments. As Aldous Huxley explored hallucinogens and penetrated nightmarish regions that would inspire his brush and pen. In 1941, André Gide published a booklet called Let’s Discover Henri Michaux.

Around 1982 he visited me in Paris. We changed a few trivial words; he was very tired. I sensed that this dialogue would be the last one.The dates of his birth and death are 1899 and 1984.

Jorge Luis Borges, prologue to A Barbarian in Asia, 1966

Jean-Francois Bonhomme

As only he would know, Borges explains how at the end of his life, Michaux felt the scientific impulse once again, the one that years before had led him to take an interest in medicine, now in relation to the world of narcotics. He had based his work on expressing the inexpressible, the meaningless and so profound in the human being that it was inherent in him and all those around him. Following this path, the self described as a sober hot water drinker, at 55 years began a series of experiments where he consumed LSD, mescaline or other hallucinogens to start a mental journey that would later try to relate in his work.

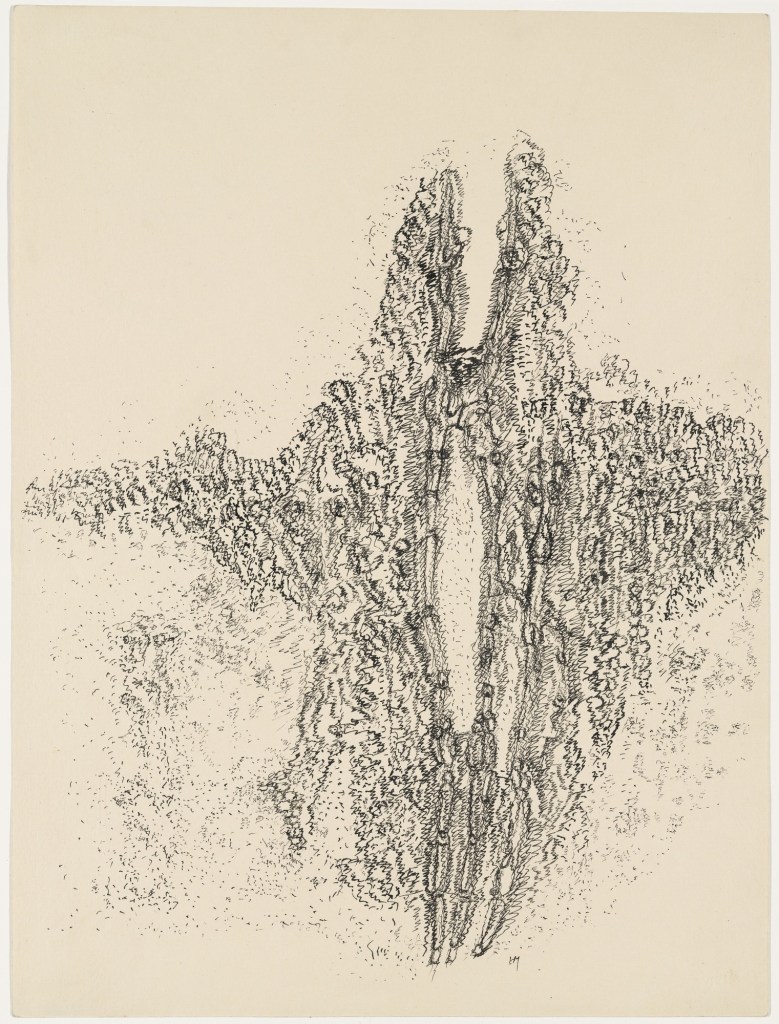

This succession, objectively obsessive and moved by a force as past as the drawings on Altamira’s walls, has given rise to a hypnotic work, perhaps not because of its beauty or its precise lines, but because of the very force and forcefulness it arouses. Perhaps because of this forcefulness, many of his works are labelled as “Untitled“, and many others were destroyed by him; because they were not born from the search but from the incisive and forceful need; the one of a sharp and sharp blow in the entrails to try to extract feelings, sensations, cold or heat, and put them on a forensic scale, which instead of needle and scale, is endowed with a pen at its end.

Mescaline Drawing, 1960

Mescaline Design, 1958

Mescaline Vibration, 1955